I learned how to code by creating plugins for Minecraft, and to this day, I believe that Minecraft has tremendous yet largely untapped educational value.

Minecraft: Education Education is certainly a great step towards realizing this potential, but for my Computer Science Principles workshop I taught at several CPS schools, I wanted something more custom and aligned with real-world coding practices than that game allowed. So, I modified Minecraft: Java Edition to add a block-based programming language and a plugin-supported narrative quest about bringing Chicago's electricity grid back online following a major outage.

Narrative

Chicago has been hit by a major power outage, and you've been tasked with bringing the city back online!

- Start in Latin School where you have a chance to learn Minecraft's controls. Navigate out to the street when you're ready.

- Follow the map you've been given to a restaurant where you can claim your personal robot, a food delivery bot that is now stranded but excited about helping you on your mission.

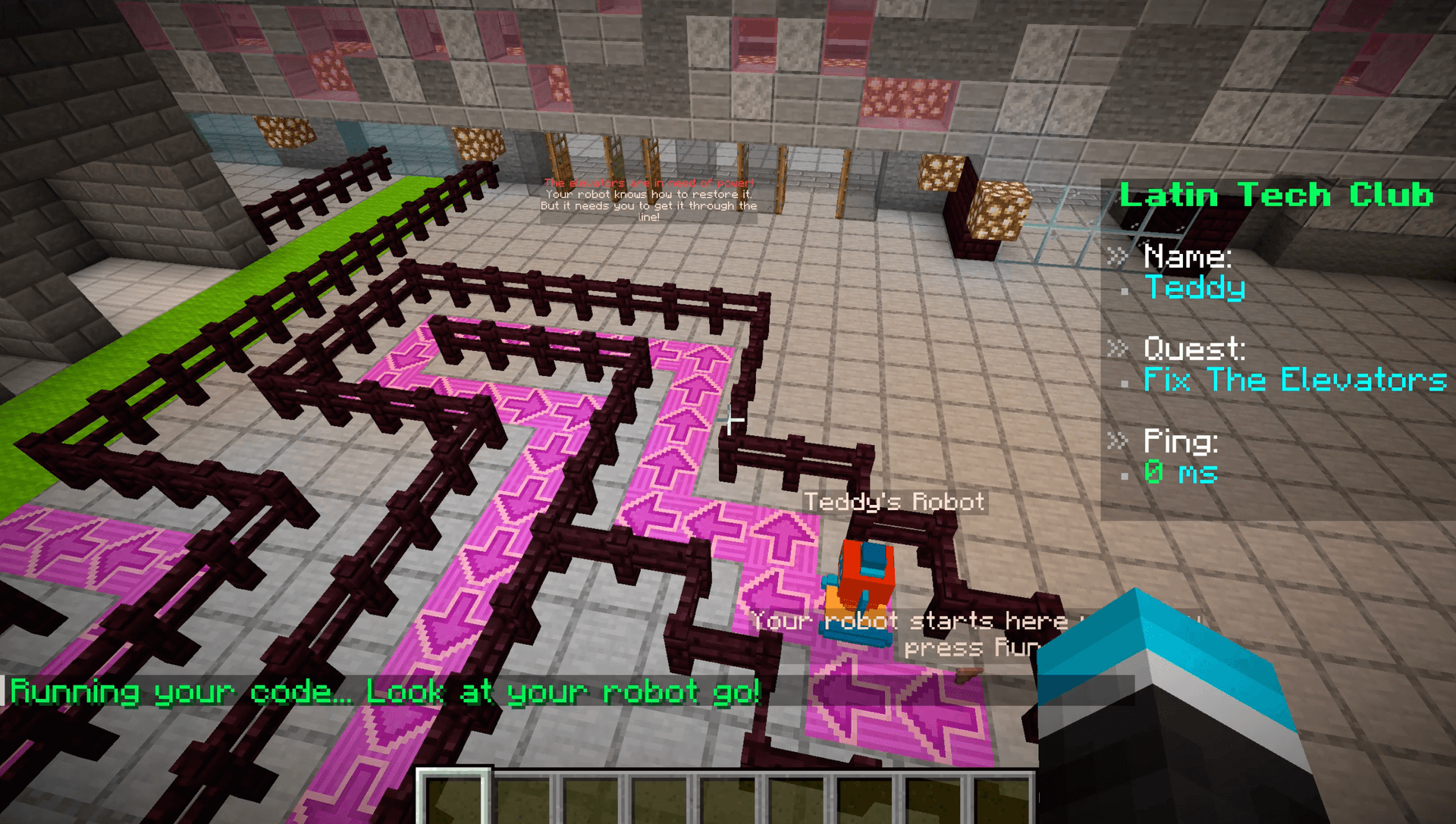

- Help your robot traverse a maze so it can navigate the streets and reach the first power station.

- Code new logic for traffic lights so your robot can do so safely without getting hit.

- Teach your robot how to identify which wires are which once you're at the station with AI.

The features below are configured in my application of this plugin to support the above narrative by adding relevant blocks to the code editor and implementing the necessary logic to support their execution.

Features

-

Customize your Minecraft name and skin in a very simple UI on each device without the need to register a separate account for each student

-

Teachers can track student progression and unlock new stages in real-time, guiding those who are falling behind or racing ahead

-

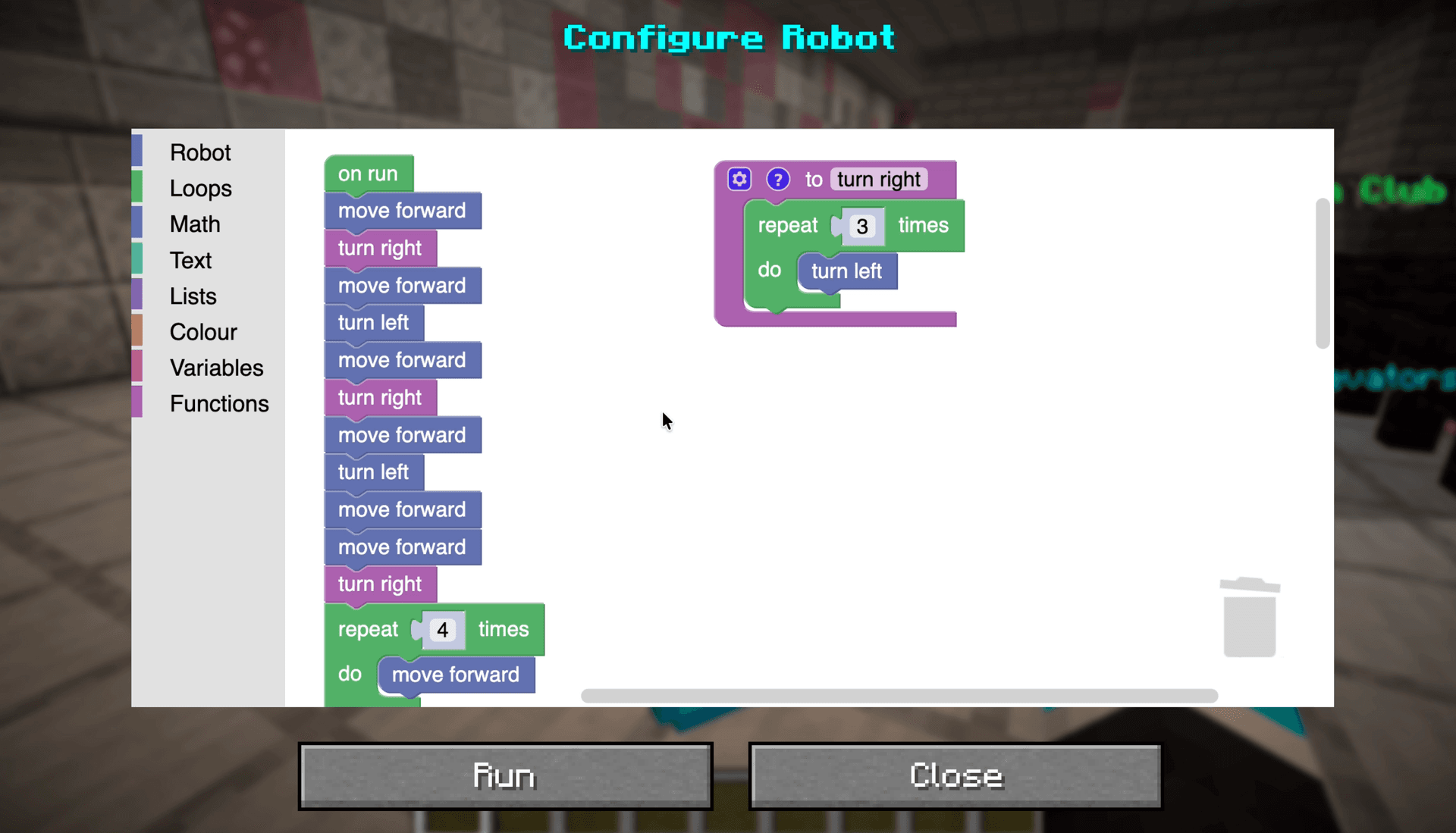

Students get assigned a personal robot once they reach a certain building on the map, which when right-clicked, opens a GUI with a Blockly-based code editor

-

Execute your code to watch your robot move around and complete its tasks

-

See other people's robots doing the same in real-time, with full multiplayer support

Engineering

Both client-side and server-side logic is built in Java with the Fabric mod loader, chosen to remove any limits from the functionality I can add to the game. If I had chosen a plugin framework instead, like Spigot or Paper, I would have severely limited my ability to add custom blocks, custom GUIs, and more.

I already had experience using Blockly to create Scratch-like block code editors, and I wanted to do something very similar for Minecraft. I explored the game's GUI APIs and how people may have done this in the past, but ultimately decided that if I could find a way to embed Blockly itself in the game, that would be the most ideal way to go. After discovering the Minecraft Chromium Embedded Framework (MCEF), I knew this would be possible: I could just render Blockly in a web view inside the game's GUI.

This then posed a new problem: I needed to somehow link that web-based editor to the in-game logic. To do this, I chose to host the web server on the Minecraft server itself using Javalin. That way, as code is edited, the serialized blocks can be saved immediately but also linked to an exact player, easily accessible by the server when they go to run it. To authenticate users, each Blockly editor is hosted on a URL with a session token included.

Since I couldn't write code for each Blockly block that actually runs in-game (it only supports JavaScript output, and also, has no access to Minecraft APIs), I needed way to capture the code's intended logic (including if statements, functions, and loops), and then execute it in a sandboxed Java environment. To do this, I set each block's code to a console.log statement, and then executed the overall JavaScript code safely with Nashorn, Java's built-in JS engine/emulator. That included appending the definition of contextual variables to the user code, so that it could be accessed within conditionals. Then, the server takes the stdout of the JS code and parses it to determine the sequence of commands that should be reflected in-game (usually entity movements or block interactions).

Interestingly, timeouts became an issue with this approach, because they didn't affect a program's stdout, only how long it took to complete. One way to solve this would have been timing the program output and matching that when reconstructing it, but then, the "Run" button would have a several-second delay before start time (and also, infinite loops fail). So instead, I overrode the default 'wait' block, creating my own that is not a setTimeout but a console.log.

Most programs ran also have their actions added to separate stacks (one per player), where every second, the server executes the top task of each stack concurrently. This way, students see each step of their robot's journey and can debug visually rather than it teleporting to its final destination instantly. Multiplayer synchronization also came practically for free since Minecraft natively replicates entity movement and other world-changing actions to all connected clients. The main work was just restricting each robot to its assigned player and designing certain structures—like the separate stack system—to support parallel execution efficiently.

The concept of quests as a unit of progression also led to several interesting design decisions. For example, Quest is an abstract Java class that expects a few properties and methods to be implemented:

- Each quest has the basics: a name and a number to identify it by in teacher UIs.

- Blockly configuration is implemented per-quest, so that different challenges can introduce different unique blocks and features.

- When a player presses "Run" in the code editor, the server expects their current quest to handle execution in-game, allowing a wide range of coding experiences and visualizations throughout the same curriculum.

- Quest-specific unlock and lock handlers determine what actions need to be taken in the Minecraft world to toggle progression to this quest when ready.

- Each quest can subscribe to event listeners, enabling dynamic logic that runs as users interact with the world in certain ways, or conditional completion of the quest.

Then, players are assigned to individual quests and can be moved between them by certain triggers or manual teacher intervention if wanted. Teachers can also see an overview of where students are in the curriculum by simply typing in a command in-game, which lists each quest's name and the players assigned to it.

Pedagogy

Several pedagogical decisions go into Blockly's configuration. For example, the maze challenge intentionally omits a "move right" block, forcing students to reason that three left turns accomplish the same thing. Then, we even pair it with human guidance, introducing the concept of functions and loops. Certain challenges also opt not to use Blockly, instead using completely custom interfaces (one meant to replicate Teachable Machine) if applicable to that challenge. Minecraft mods truly makes anything possible to teach in-game.

The entire TCVMC curriculum is also built on experiential learning principles. The story is engaging, the quests are challenging but not overwhelming, and the game is fun and rewarding to play given its multiplayer nature. Most importantly, we aren't introducing abstract concepts in a silo, we're introducing them in a context that reveals their practical applications and power.

Reflection

I've taught this game to dozens of students, and each one loves how engaging of a format it is for learning computer science. They get to see their code and that of their classmates ran in real-time, which is very rewarding because it makes CS feel like a craft—one that they can use to do great things.

Seeing Minecraft used in this creative way has also inspired lots of students who were previously only familiar with the game for its survival mechanics or fighting minigames. Many asked about how we added robots to the game, or how we imported a 1:2 replica of Chicago into our world.

Screenshots